Names, Norms, and Law: Legal Perspectives on the Persian Gulf Controversy

For more than half a century, the name of the Persian Gulf has been at the center of one of the world’s most persistent diplomatic and cultural disputes. What began as a disagreement over terminology has evolved into a test of how international law responds to historical truth. Iran and several Arab states continue to contest the rightful name of this body of water, one side invoking centuries of consistent usage in treaties and maps, the other promoting an alternative political identity through the term “Arabian Gulf.” Behind this linguistic conflict lies a deeper question: can political narratives reshape facts that international law has long recognized? This question gained renewed attention in October 2025, when U.S. Representative Yasmin Ansari introduced the Persian Gulf Act, a bill requiring all federal agencies to use only the historically-established term Persian Gulf in official U.S. documents. While the Act may seem symbolic, it carries significant implications for the legal protection of historically-verified names and for the role of states in preserving factual accuracy within international discourse. In effect, it turns a domestic legislative measure into a statement about global norms, one that aligns the United States with the longstanding policies of the United Nations and UNESCO. This article explores the Persian Gulf Act as more than a national gesture. It argues that reaffirming the name Persian Gulf reflects a broader legal and ethical commitment: defending the integrity of historical truth against revisionism. In an era when politics increasingly challenges established facts, safeguarding accurate geographical nomenclature becomes part of preserving the rule of law itself.

1. Historical Continuity and Documentary Evidence

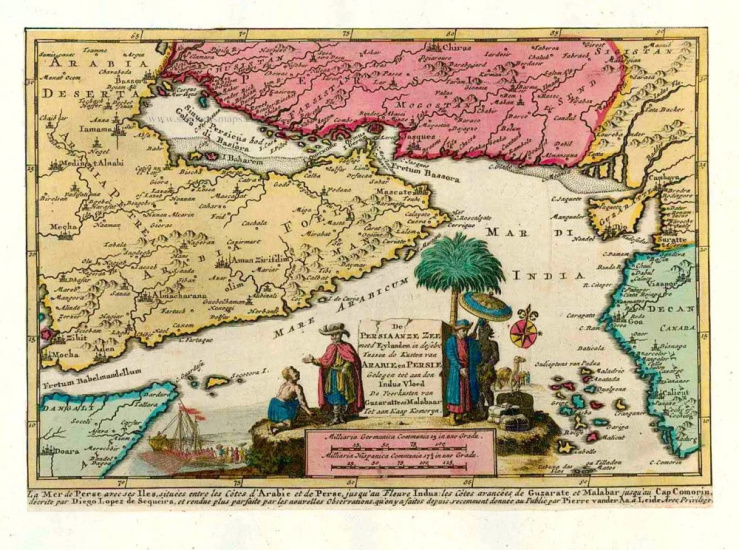

Few geographical names have shown such remarkable endurance through time as the Persian Gulf. From the writings of classical geographers like Ptolemy and Strabo to the great scholars of the Islamic Golden Age, among them Istakhri, whose Ṣuwar al-Aqālīm mapped the known world the same term has persisted. Whether written as Sinus Persicus in Latin or Khalīj al-Fārisī in Arabic, the phrase has described this stretch of water for well over two millennia. The stability of this name is not a matter of national sentiment; it is a matter of documented fact. A 2006 working paper of the United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names examined more than six thousand maps produced before 1890. Nearly all of them referred to the region as the Persian Gulf, with only a handful using short-lived alternatives such as “Basreh Gulf” or “Arabian Gulf.” A few maps used “Gulf of Iran,” but even those reinforced the geographical association with Persia rather than with any other polity. In the modern era, this historical continuity has been formally-recognized by international institutions. The United Nations Secretariat, in a letter dated 18 March 1994, reaffirmed that the only established and acceptable designation for this body of water is Persian Gulf. UNESCO followed a similar approach in its 1987 circular, directing all member states and affiliated organizations to use the same name in their cultural and cartographic materials. The International Hydrographic Organization did likewise in its Limits of Oceans and Seas (1953), referring to the area as “Persian Gulf (Gulf of Iran).” Later efforts by some Arab governments to change the term in subsequent revisions failed not out of politics, but because such a change lacked international consensus, a basic requirement in customary international law for altering any geographic designation. Taken together, these records establish the Persian Gulf not as a contested term but as a recognized legal and historical expression one that carries normative weight and institutional legitimacy.

2.The Legal Dimension: Stability as a Principle in Geographical Names

In international law, names are never neutral. They are more than labels on a map they are part of the legal language through which states recognize one another and define their borders, treaties, and histories. A geographical name that appears in legal instruments carries with it a certain weight of recognition. This is why the Persian Gulf is not simply a matter of geography but one of law. Under Article 31(1) of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969), the terms used in treaties must be interpreted “in good faith” according to their ordinary meaning and context. This rule protects the established and widely-accepted usage of terms against reinterpretations that serve short-term political aims. The International Court of Justice has followed this logic in its own practice. In the Oil Platforms case (Iran v. United States, 2003), the Court referred repeatedly to the “Persian Gulf,” reflecting its status as the accepted geographical and legal term. The same terminology appears in several UN Security Council resolutions including Resolution 687 (1991), which helped conclude the Iraq–Kuwait conflict showing a consistent institutional use across decades and across forums. Behind this consistency lies what international geographers and lawyers often call the principle of stability of geographical names. The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names has long held that place names are part of the international legal order. Once established, they cannot be changed unless there is clear and universal acceptance of a new term something that has never occurred in attempts to replace Persian Gulf with “Arabian Gulf.” Seen through this lens, the endurance of Persian Gulf is not a coincidence of history. It reflects a deeper commitment to legal continuity the same kind of continuity that international law protects in matters of statehood, borders, and identity. A name, once rooted in law and collective recognition, becomes part of the architecture of international order itself.

3. The Politics of Naming: Power, Identity, and International Order

The controversy over what to call the Persian Gulf is not just about maps it is about identity, memory, and political power. The term “Arabian Gulf” did not emerge from historical usage; it was a political invention of the mid-twentieth century. It appeared alongside the wave of Pan-Arab nationalism led by Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser, who sought to create a shared Arab identity across the region. As Joshua Teitelbaum notes in The Rise and Fall of the Arab Gulf Narrative (2006), the new term was “a project of ideological unification rather than geographical accuracy.” Colonial politics helped spread this new vocabulary. British officials such as Sir Charles Belgrave and intelligence officer Roderick Owen experimented with alternative names for strategic reasons during the final decades of empire. Yet even within the British Foreign Office, official documents, maps, and diplomatic correspondence continued to use Persian Gulf. The change in terminology, though politically-charged, never gained formal recognition in law or in the records of international institutions.

Today, the same politics of naming continues in different forms. Some Arab governments have promoted “Arabian Gulf” in media campaigns, sports tournaments, and school materials, hoping to normalize a politically-motivated expression. But international law draws a clear line between cultural advocacy and legal fact. The lex lata the law as it currently stands recognizes only one legitimate name: the Persian Gulf. This enduring debate reveals something deeper about how power and identity interact in international relations. Names are not just symbols; they are claims to history. When politics tries to rewrite the language of geography, law becomes the guardian of truth. In that sense, the story of the Persian Gulf is also a story about the resilience of evidence over ideology a reminder that, even in the age of competing narratives, facts still matter.

4. The Persian Gulf Act: A Legal Reaffirmation of Historical Truth

When the Persian Gulf Act was introduced in the U.S. Congress, it might have seemed like a small symbolic gesture a domestic bill about a name most people take for granted. But for those who follow the politics of geography, this proposal touches a much larger story: the link between historical truth, international law, and the way nations choose to represent the world. At its core, the Act asks every federal agency in the United States to use only the term “Persian Gulf” in official documents. On paper, this is a matter of consistency. In practice, it echoes a decades-long international consensus shared by the United Nations Secretariat, UNESCO, and the International Hydrographic Organization that “Persian Gulf” is the only historically and legally recognized name for that body of water. By aligning its own terminology with that of these institutions, the United States would be reaffirming a broader legal principle: that names, like treaties, carry the weight of truth and continuity.

The implications go beyond semantics. If enacted, the Persian Gulf Act would signal that the United States takes seriously the preservation of factual geography in an age when disinformation can blur even the contours of a map. It would also offer an example to other governments of how domestic law can quietly reinforce global norms in this case, the norm of historical accuracy in international nomenclature. Far from favoring one regional actor over another, the Act upholds a principle that transcends politics: accuracy matters. There is also a diplomatic layer to consider. By choosing to codify a historically-verified name, Washington would be sending a subtle message about its commitment to rule-based international order and to the institutions that safeguard it. It could help rebuild trust in multilateralism at a time when facts themselves often become contested terrain. Within the Middle East, the move might even open new avenues for dialogue shifting attention from rivalry over words to cooperation grounded in legal respect and historical truth.

In the end, the Persian Gulf Act is less about nostalgia than about integrity. It is a reminder that the way we name the world reflects the kind of international order we want to preserve one anchored in evidence, law, and respect for history. In a time when maps can be redrawn by propaganda as easily as by software, insisting on factual nomenclature becomes more than a technical choice; it becomes a quiet act of principled diplomacy.

5. International Law and the Ethics of Historical Truth

International law, at its deepest level, is more than a collection of treaties or procedural rules it is a living archive of our shared memory as a global community. Every term, every name, carries within it traces of human history and collective understanding. To alter such names is not a matter of semantics; it is an act that reshapes how the world remembers itself. When the name “Persian Gulf” is distorted or replaced, it is not only geography that is misrepresented it is the documentary fabric of civilization that begins to fray. The defense of historical names, therefore, is not about nostalgia or national pride; it is about ethical responsibility. International law has long recognized this duty through a constellation of overlapping principles. The principle of good faith demands that states act with honesty toward established facts. The doctrine of legitimate expectation protects the continuity of consistent usage in international relations, ensuring that words retain their meaning across time. And the principle of cultural heritage preservation, embodied in UNESCO’s conventions, affirms that safeguarding history whether in monuments, manuscripts, or maps is part of the moral architecture of international cooperation. When these principles are taken together, they reveal a profound truth: changing a name rooted in centuries of usage and legal recognition is not a benign political act it is a breach of trust within the international community. Just as arbitrarily redrawing borders destabilizes the territorial order, rewriting the language of geography destabilizes the moral order of law. Defending the name “Persian Gulf” is, in that sense, an act of epistemic justice a commitment to truth as a shared heritage of humanity. It is a reminder that in the vocabulary of international law, accuracy is not an accessory to politics but its conscience.

Conclusion

The name Persian Gulf is not a phrase from a distant past; it is a living part of international law. It appears in treaties, UN documents, court decisions, and maps that record the shared memory of nations. Its endurance is not the result of nostalgia, but of legal continuity and collective recognition. Like the flow of the gulf itself, its course cannot simply be redirected by political slogans or temporary campaigns. The Persian Gulf Act offers more than symbolic reassurance. It reminds the world that accuracy in naming is a form of respect for history and that in law, truth still matters. At a time when historical narratives are being shaped and reshaped by power politics, the insistence on factual terminology becomes an act of legal integrity. Reaffirming the Persian Gulf means reaffirming the idea that international law must remain anchored in verifiable truth, not in political convenience. The Persian Gulf thus stands as more than a geographical term; it represents the quiet persistence of law over ideology, and continuity over revisionism. Some names, like certain rights, are inalienable. Preserving them is not about the past it is about protecting the foundations of international order in an age when truth itself is under pressure. In that sense, the defense of the name Persian Gulf is a small but meaningful stand for the rule of law, and for the integrity of fact against the tide of disinformation.

* MohammadMehdi Seyed Nasseri holds a PhD in Public International Law from Islamic Azad University, UAE Branch (Dubai). He is a researcher at the Center for Ethics and Law Studies, Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran; and Lecturer in International Law at the University.