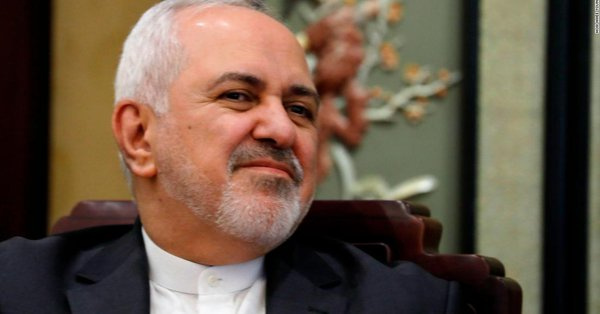

Why Zarif's Untimely Departure Was Harmful to Iran's Interests

As expected, the news of resignation of Iran's foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, has been greeted with a sigh of relief in Tel Aviv and Washington. "Good riddance," Israel's Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, recipient of major diplomatic blows by Zarif, has responded, while Benjamin's allies in the White House have confined their joy to a less conspicuous expression as part of their relentless confrontational policy against Iran. No doubt, the likes of Bolton, Pence, and Pompeo and even Trump himself, who was in a perpetual twitter war with Zarif, are elated that their formidable adversary, who skillfully outshined them at major international conferences such as the recent Munich security conference, is now out of the picture. For Iran, on the other hand, this represents a major setback for Iran's soft power diplomacy and the current Iranian struggle against its array of foreign adversaries on the international stage.

In his recent trip to China, Zarif's counterpart Wang Yi greeted him at the airport and praised him as a "hero" who is well-known and respected by people in China. In a certain sense, at the time of his resignation, Zarif was at the pinnacle of his international fame, in light of his fiery anti-American speech in Munich that went viral and was by all accounts the highlight of the security conference. Coinciding with the new American interventionism in Venezuela, Zarif's defense of Iran's "self-determination" resonated with a broader reality in global politics today, featuring a unilateralist and aggressive American imperial power targeting assertive developing nations such as Iran and Venezuela and Cuba and Nicaragua, often managing to coerce a few nations along its ruinous path. Indeed, increasingly Zarif had acquired the status of a third world heroic statesman, expressing the political discontent of not only Iranians but also the rest of the developing world, in the fine tradition of other non-aligned leaders since WWII.

But, of course, it is the question of how will Zarif's exit impact Iran's current struggle against the unjust American aggression that matters most. For the fact of the matter is that Iran today is under an American siege and must therefore utilize all its hard and soft power resources in this historic struggle, otherwise it risks undermining its own efforts, all the more reason not to allow domestic factionalism have paralyzing effects on Iran's foreign policy, or the protean values of "parallel diplomacy" outweigh its complementary contributions by undermining the coherence and integrity of Iran's foreign policy machinery. This is, indeed, a tall task since because of the multiple foreign crises in Iran's vicinity, certain aspects of Iran's foreign policy have been "securitized" and have resulted in an administrative bifurcation that has its pros and cons. On the con side, this phenomenon runs the risk of certain atrophy of the formal apparatuses of Iranian diplomacy, which can in turn result in sub-optimal performance of those apparatuses. In this connection, Zarif's resignation ought to serve as a wakeup call that this bifurcation and diplomatic parallelism require a fresh examination and, perhaps, a re-construction in the direction of greater internal coherence.

Chances are that President Rouhani will reject Zarif's resignation and reach out to him to 'heal' the wounds, so to speak, which is in the country's diplomatic interests at this crucial juncture. The critics of Zarif often ignore the fact that regardless of who replaces Zarif, the key problems facing Iran's foreign policy decision-making process remain essentially unchanged, and it takes the dexterous diplomatic hands of Iran's top diplomats to seek apt solutions for such problems as European tardiness in implementing their JCPOA obligations, or fighting American power at international forums. Thanks to the relentless efforts of Dr. Zarif and his deputies, Iran's regional policy in the past few years has much to brag about, reflected in Zarif's highly successful recent tour of the region, which is partly attributable to the keen attention given by Zarif to the priority of Iran's neighbors.

No doubt, the above-said does not mean that Iran's foreign policy under Zarif has been problem free and Zarif himself has admitted to certain shortcomings. But, these must be assessed correctly in terms of the excess load of responsibility and tasks shouldered by the foreign ministry in a perpetual crisis situation, and the enormity of external challenges posed by the axis of American-Israel-Saudi power. In other words, it is unfair to place the blame on the embattled foreign minister for the problems generated from outside Iran's borders, requiring skillful diplomatic countermeasures at regional and global levels.

In conclusion, an objective balance sheet of Zarif's unique contributions is presently needed, and sadly still missing, clouded by the heat of domestic politics, which Zarif dutifully tried to insulate from the country's foreign policy for the sake of latter's prerogatives. That noble effort must be continued by whoever replaces Zarif, and hopefully Zarif can re-emerge on a healthier footing and continue to represent Iran in the international scene as he has until now with superb deftness, wisdom, experience, and diplomatic craft. Iran's enemies must be deprived of their current joy in seeing Iran self-deprived of one of its finest diplomatic assets, one that showed the limits of American diplomatic power by an articulate and first-rate Iranian diplomat schooled in international diplomacy.