Fordow Proving More Difficult To Solve

August 7th, 2014 – Azadeh Eftekhari

The Iran-P5+1 nuclear negotiations have been extended until November, leaving the two sides four months to bridge the gaps and resolve their differences in order to reach a final agreement. Iranian Diplomacy recently spoke with Peter Jenkins, a former British diplomat who was the British Ambassador to the IAEA from 2001 to 2006, about the future of Iran’s nuclear dossier and what is needed to reach a comprehensive agreement.

After long discussions in Vienna, some experts say Iran’s insistence on industrial scale enrichment was the main obstacle toward reaching a final deal. What does industrial enrichment mean and how much does Iran need this type of enrichment?

Industrial enrichment means enriching uranium hexafluoride to a level and on a scale that can enable Iran to supply reactor fuel to the operators of power and research reactors. The weak point in the current Iranian position is that it has no practical domestic need for such fuel and is unlikely to be able to win orders to supply consumers elsewhere in the world. Iran may be able to develop a domestic need but that will take several years. Iran talks of supplying the Bushehr reactor after 2021, but it is improbable that Rosatom, which built much of that reactor, will be ready to give Iran the proprietary information needed for the production of Bushehr fuel to be safe and to the correct specification.

That said, there is no basis in international law for outsiders to impose on Iran a particular scale of enrichment for peaceful purposes or to impede Iranian development of an enrichment capacity that will, one day, be commensurate with Iran’s practical needs.

Mr. Zarif recently said Iran does not need 190000 SWUs until the next 2 years. Will this position lead to an improvement in negotiations?

Yes, it ought to make a difference. There will be no deal unless Iran recognises that, whatever its legal rights, it would be acting wisely if it were to volunteer a policy of restraint – that is, if it were to undertake to refrain from expanding its enrichment capacity until after the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has provided the international community with an assurance that Iran’s nuclear activities are entirely peaceful in nature and intent.

One idea is changing the centrifuges’ generation. Is this useful?

I think you are referring to the introduction of more advanced centrifuge models. This can be helpful in as much as it enables Iran to advance technologically towards the goal of self-sufficiency in nuclear fuel supply. But it would be unhelpful if the introduction of new models were not compensated by the withdrawal of older models during the non-expansionary, interim period suggested above.

Is it possible to limit Iran’s nuclear capacity without insisting on decreasing the number of centrifuges?

One can limit capacity in the sense that Iran can undertake not to add to its current installed and operating capacities. Such an undertaking would amount to an extension of the undertaking given in November 2013. One could envisage a progressive reduction in capacity if Iran were also to undertake, during the interim period, to refrain from replacing centrifuges when they break down (as all centrifuges tend to do).

Some non-nuclear weapon states such as Japan do not produce nuclear fuel at home. Why does Iran want to have its own fuel?

Essentially, because Iran has had bad experiences which lead the government to believe that it cannot rely 100% on foreign suppliers of reactor fuel. Also because Iranians see self-sufficiency as a demonstration of technological prowess; the goal of self-sufficiency was first set in the 1970s when Iran was seeking to regain its position as one of the more prosperous and influential of Asian nations. Other states have greater confidence in the reliability of the global nuclear fuel supply market and have opted to acquire prestige in other ways. Whether Iran is also hedging against the possibility that one day the nuclear non-proliferation regime will collapse, as Japan is widely believed to have done by accumulating a stock of plutonium, I cannot say. I have seen no evidence that this is a motive, but the possibility cannot be excluded.

What are the bottom lines for Iran and the US in nuclear talks and reaching a final deal?

I really don’t know. It would be surprising if both sides did not regard their bottom lines as state secrets! But on the evidence to date, I fear the US bottom line may be over-ambitious. I fear they want to extract concessions from Iran that no Iranian government can afford to make, even if those concessions are richly reciprocated. In my view this strategy is illogical. The US administration wants to use those concessions to persuade Congress that Iran could not produce a nuclear weapon under any circumstances. But even drastic reductions in Iran’s installed and operating centrifuge numbers would not suffice to satisfy those in Congress who believe that Israel’s security requires the complete elimination of Iran’s fuel cycle capabilities – at the very least.

How about Fordow and the heavy water reactor in Arak? With recent statements from Mr. Araghchi that said deep differences remain, do you think both sides can solve the problem?

I am under the impression that the parties are close to agreement on Arak. Vice-President Salehi made a public statement in June which suggested that the AEOI was working on ways of reducing the plutonium content of the spent fuel that the reactor will produce once it is operational. If that is the case, I would be surprised if it were not an acceptable solution in the context of a final bargain.

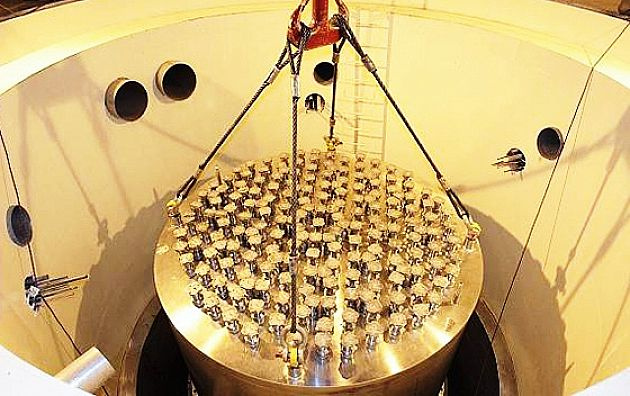

Fordow is probably proving more difficult to solve. The US would like to see Fordow closed. I can’t imagine that being acceptable to Iran. There has been speculation that a compromise could be for Fordow to remain open but be used as a centrifuge R&D centre. But I can imagine even that being problematic, since the US will not be keen on such R&D taking place.

What are the remaining gaps and do you think 4 months is long enough for each side to bridge the gaps?

There may still be differences in relation to claims that Iran is developing missiles that would be capable of delivering nuclear payloads. And the US is probably linking the pace and scale of sanctions relief to the value of the confidence-building concessions, e.g. on centrifuge numbers and the duration of an interim period, that Iran is ready to offer.

Four months will be enough if the US can bring itself to accept that its obsession with making “break-out” (Iranian production of enough weapon-grade uranium for one device) impossible is misguided, and if the US can shift to greater reliance on the barriers to proliferation that the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty provides, augmented by whatever confidence-building measures Iran is ready to offer. It will not be enough if the US mind-set remains unchanged – that is, if they will not recognise that potential threats are better averted by addressing a potential adversary’s perception of his security interests, than by addressing his material capabilities.