Two Viewpoints on Reconstruction in Iran

Article by: Dr. Hormoz Homayounpour

In this article, we will discuss reconstruction in Iran based on the following two books:

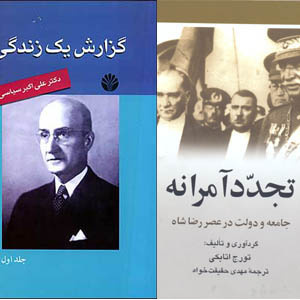

A Life’s Report, written by Dr. Ali Akbar Siasi (First Volume), Akhtaran Publications, 319 pp., Tehran 2007.

Prescribed Modernization (A Series of Articles), collected and written by Touradj Atabaki, translated by Mehdi Haghighatkhah, Ghoghnoos Publications, 286 pp., Tehran 2007.

Hopes fore growth and development in this region of the world were born about two hundred years ago. Before this, the systems of life and the government were rather “eastern”.

Everybody was more or less satisfied with what they had and social and individual lives were moving forward with a rather slow pace, a reminder of lengthy periods of time in history. But three main events led to people becoming aware of their profound backwardness, heavy blows being dealt upon them and causing them to become more conscientious.

These three events were: the defeat of the Ottomans at the hands of Tsar-led Russia (1768-1774, 1787-1792), Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt (1798), and the defeat of Iran by Tsar-led Russia (followed by the Golestan Treaty in 1813 and later, the Turkmenchay Treaty).

Therefore, the West’s appeal attracted everybody’s attention. People asked themselves why European countries should grow but eastern nations should remain in poverty and misery.

Little by little, the people’s awakening led to major political and social changes: Egypt, led by Mohammad Ali Pasha, began its path toward reconstruction, an era of law and order and regulations started in the Ottoman Empire, and Iran’s metamorphosis began with the Constitutional Revolution. These changes overshadowed the idea of constitutionalism, the rule of law, the creation of a judicial system, and the extinction of feudalism and authoritarianism.

Even though the majority of people were not aware of the exact definition of these concepts, the angst to achieve them ran deep in the hearts of all and modernization became a popular idea.

A brief introduction of the two books

The story of how modernization and reconstruction grew as a concept in Iran is a long and complicated one.

The first book, “A Life’s Report”, is the autobiography of a rather serious person and a man of principle, a man who is mostly known in Iran as the president of Tehran University. For many years, he worked to protect the independence of this institution and the reconstruction movement, but ultimately, he was unfortunately unsuccessful.

In this book, he talks about Tehran in the old days and the city’s miserable conditions. He also talks about his education in Tehran and Paris, the widespread reconstruction he observed on his return to Iran, and the different jobs and responsibilities he had, from being a Political Science professor at Tehran University to his positions in public and ministerial offices.

Apparently, this book has a second volume and we hope that it will be published in Iran soon. In this article, we will only mention a few parts that talk about “reconstruction”.

The second book, Prescribed Modernization, consists of a foreword and seven long chapters or articles written by Touradj Atabaki, Mohammad Ali Homayoun Katouzian, Houshang Shahabi, and four foreign researchers.

In these articles, the authors describe the situation of society and government during the rule of Sardar-e-Sepah, later known as Reza Shah. The articles also talk about political and social conditions during this era and about the formation of a modern army, dress code regulations, language reforms, and Vosuq-o-doleh’s contract.

It seems that this book also had three other chapters, but they have not been printed because they deal specifically with Turkey (based on the publisher’s notes). It would have been much better if they had not omitted these parts, since it would be very interesting to know a little bit more about the events that took place in our neighboring countries during the same time. It is in my opinion even necessary for the readers to know more about these countries because they probably have enough information about the events in Iran.

The Beginning of Reconstruction in Iran

When speaking of the beginning of reconstruction in Iran and how it came to be, both books talk about the same thing and they set the date to a few years before 1922 and the Reza Shah’s reign and Sardar-e-Sepah’s time as minister. But the books differ in details. “A Life’s Report” is rather one-sided, but Prescribed Modernization mostly talks about matters through an economic viewpoint.

Talking about his trip to France along with a group of 22 students (1921, his first trip abroad), Dr. Siasi writes that “our trip from Tehran to Anzali took 5 days, because… during that time…. motorcycles, buses, and automobiles did not exist in Iran. The main means of transport were wagons and carriages (horse-drawn carriages in Tehran) in cities and Palkis and Kajavehs and Delijans.” (p.51)

However, when they were sent back to Iran, due to the start of World War I and the government’s lack of budget, after a five year stay in France, the governor of Gilan sent them to Tehran with carriages (1926): “Five years ago, I went from Tehran to Rasht with a delijan, but now with the minor advancements that have taken place in our country, we were able to do this trip with carriages.” (p. 60)

He also writes about the conditions in Iran before 1922:”The streets and alleys in Tehran, the kingdom’s capital, were dark and narrow and during winters they were filled with mud and during the rest of the year, they were full of dust… asphalt and water pipelines were non-existent.”

“People filled their water reservoirs with the polluted water of streams and they used this water to drink, to wash their hands, to bathe, etc… there was no mayor’s office, no registry offices… the bumpy and dirty roads connecting cities were not safe… there was no army… all there was, was a gang of Kazakhs led by a Russian colonel… the government’s treasury was empty.

The government often asked the Britain and Iran Oil Company for money to be able to pay its employees’ salaries; influential businessmen would often affiliate themselves with the Soviet and British embassies to protect their wealth and their status; foreign powers would dictate custom tax rates so that they could import their products without paying almost any custom taxes.” (pp. 79-81)

In Dr. Siasi’s opinion, “it is rather difficult for people who were not alive before 1921 to get a feel of the conditions at that time through this short article.” (p.79)

It is for all these reasons that he has high praise for Reza Shah. He formed the “Young Iran Council” with a group of his friends, because they could no longer tolerate the country’s catastrophic state. They believed that the old and weary Iran would be able to become young and strong again by accepting the new civilization.” (p.84)

A short time after this council was established, Sardar-e-Sepah, the country’s prime minister, asked to meet them. “The council accepted Sardar-e-Sepah’s invitation, although they could not do otherwise.” (p. 86)

During this meeting, after reading the country’s constitution to them, Sardar-e-Sepah was not very kind to them and he said, “Fine, you can do the talking but I’m the one that will enforce, I reassure you, and I will go as far as to promise you that I will make all of these dreams come true.” (p.86)

Dr. Siasi writes: “We did not take his promise seriously and we were not hopeful that our hopes and dreams would become reality, especially during a short period of time [However, history showed that this great man was not bluffing and that he had not given false promises, because during his rather short time in office, twenty years to be precise, he was able to make all our wants a reality.].” (p.87)

The Other Side of the Story

Even though Prescribed Modernization also accepts that “during his twenty years' reign, Reza Shah was able to accomplish all that which intellectuals were talking about” (p.18), it states that “Reza Shah’s dictatorship was transformed into an autocracy after two years and a while after that, it changed into an arbitrary rule.” (p.19)(and also in Dr. Homa Katoozian’s article in pp.23-64).

Based on Mokhabber-o-saltaneh Hedayat’s memoirs, Katoozian writes: “During the Pahlavi dynasty, no one had the right to decide on their own. All matters first had to be addressed to the Shah and things would be done based on the Shah’s request.” (p.47)

Therefore, “there were no real politicians with a will to fight back”; one by one, they would be eliminated (Teymour Tash, Sardar As’ad Bakhtiari, influential clergymen, Solat-o-doleh Ghashghaei,…) or sent into exile (Dr. Mosaddegh, Ghavam-o-saltaneh,…).

In the opinion of Touradj Atabaki, “In the European community, modernization was growing fast and it was followed by a growth in individualism and the establishment of a civil society, but things were completely the opposite in Ottoman Turkey and Iran.” (p.8)

Katoozian writes, “Throughout the history, totalitarianism has always been the typical form of rule in Iran, keeping in mind that dictatorship only lasted four centuries in Europe.” (p.23)

She then writes, “In Iran, the government could do anything it wanted, including the illegal and forceful taking of people’s lives and possessions.”(same page)

In Europe, leaders and governors would represent the society’s important classes. However, “in Iran, the government was completely separated from society” (p.23) Therefore, revolutions in European countries would be against ruling classes, but revolutions in Iran were against the entire government and system and these revolutions were in fact a vicious circle of “dictatorship, revolts, dictatorship”. (same page)

Therefore, even though during Reza Shah’s reign the majority of people and intellectuals supported his reforms in the beginning, these relations began to fade with time; the military began to meddle in everything in Tehran and other cities through violence and corruption and the government was in a way against the people. This was so much so that when the Allied forces occupied the country in September 1941, people from all social classes celebrated Reza Shah’s departure.

A few of the topics that Prescribed Modernization talks about are: Reza Shah and army officers taking people’s possessions, the assassination and exile of well-known national politicians, the elimination of the last traces of freedom and democracy, the imprisonment of anybody who did not agree with the government, the centralization of all powers and affairs, whether foreign or domestic, in the hands of one individual, and the spread of suppression accompanied by corruption and dictatorship.

In fact, in the beginning, no one “could believe how easily things worked out for such a “usurper". (p.40)

Quoting Ali Dashti, a member of parliament at that time, “In these last twenty years, the principal of ownership (which is one of the main ideas of human rights) has not been respected, people have been sent to prison and their possessions have been taken. Then what is the difference between a thief and the government.” (p.50)

The Importance of a Dress Code and Hats

The article “Dress Code Regulations for Men in Turkey and Iran” (Houshang Shahabi, pp.183-221) is another one of Prescribed Modernization's interesting articles.

In fact, one would never think that the clothes a person wears or the type of hat he or she puts on would have important and serious social, political, and cultural consequences.

In Shahabi’s opinion, “this matter is one of the most obvious aspects of the two governments to modernize the two nations. This was rather like the reforms of Peter the Great with respect to the Russian people’s appearance.” (p.183)

Because of the opposition of Turkey’s clergy, different laws were passed in that country, forcing people to dress in a more modern way. “But opposition to the clergies was not the only motive for dress code regulations; nationalism and nation-building were also two important factors.” (p.205) Shahabi states, “Nationalism consisted of two aspects: Domestically, a powerful government had to be formed to stand up against foreign invasion, and internationally, the country’s independence had to be guaranteed against Europe. The first would fulfill the motive for uniformity, the second Europeanisation.” (p.206)

This subject, i.e., a kind of contradiction, makes up most of the content matter of this book.

In the article “Language Reforms in Turkey and Iran” (John R. Perry, pp.223-252), we see the effects of this chaos-causing contradiction again, a matter that “in fact started around a thousand years ago” (p.225), with the ideas of the likes of Ibn-i-Sina and Birouni. The dilemma with regards to language traditions seems to exist even today; this might be the same old battle between tradition and modernity.

Because of the close tie between “Clearing Ambiguity: Vosuq-o-doleh’s Foreign Policy” (Oliver Ballist, pp.253-282) and diplomacy and foreign policy, it is probably more fitting if the article’s analysis is done more precisely in another article, something I hope my colleagues at the Iranian Diplomacy website will do later on.