Elections, Mass Media and Short-term Thinking in Foreign Policy: The Case of the Afghan War

On 16 December, 2010, President Obama claimed that U.S. Afghan strategy is "on track" and that the U.S. can embark on a "responsible" troop withdrawal by July 2011. This has already made a vast number of Afghan observers, particularly within Afghanistan, quietly voice their discomfort with such a hasty announcement—not least because the Administration strategic review is based on overtly optimistic projections.

Although the Taliban now appears to have lost a great deal of power and operational capabilities, it should not be forgotten that one main reason for this power deficit is Afghanistan’s harsh winter. It is very likely that the Taliban will begin launching new offensives in and around the spring, thereby crushing the U.S.’ and its allies’ hopes for an early withdrawal. This is why one cannot help but be suspicious of the President’s main motives and the strategic depth of his Afghan policy.

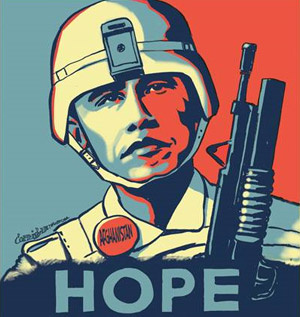

Given the American public’s increasing disillusionment with the war as well as the upcoming presidential election, scheduled for November 6, 2012, it becomes at least an interesting analytical exercise to investigate the extent to which elections and mass media in democracies hinder long-term strategic thinking and foreign policy making.

This becomes all the more interesting if/when explored within the geopolitical context of the rise of China and its implications for the United States: a rich, authoritarian state well-positioned for long-term planning due to its relative disregard for public opinion versus a democracy whose leaders’ main task is the appeasement of the public so as to ensure their hold on power.

A key element and perceived strength of democratic governance is that succession is determined by a democratic electoral system in which citizens have an equal say in whom their next leader will be. While this is cherished as a positive and progressive development among functioning democracies, it also has a profound impact on a country’s foreign policy. Politicians in democracies must appear popular to their constituents in order to safeguard their election and re-election. In terms of dealing with transnational threats, this severely limits the ability of politicians to tackle/address them effectively.

As such, there is a constitutionally rooted problem that seriously affects the conduct of foreign policy. Crises can radically change the normal political calculus and once a crisis turns into a prolonged, costly commitment, domestic political considerations are likely to take priority.

President Obama has now inherited two conflicts and is seeing his own approval rating slide downward as casualties continue to rise in Afghanistan, despite the military surge earlier last year. Domestically, the uncertainty of a recovery for the US economy is further pressuring Obama to find some sort of face-saving exit strategy to end the costly US involvement in Afghanistan.

Many have argued that long-term developmental commitment, such as the provision of health care and basic education services, is the best way to win the hearts and minds of ordinary Afghans and thereby thwart the recruitment efforts of the Taliban and their approval among the local population. However, policy makers in Washington and other Western capitals seem to have settled on short-term strategies more popular with the general public, such as limiting the number of forces in Afghanistan. Sadly, these short-sighted policies will allow the Taliban to regroup and regain the initiative in the coming years.

This means that democracies are structurally at a disadvantage in trying to develop and sustain policies that require a mastery of complex issues, and call for consistency and a long-term vision to enhance the prospects of success. There are electoral pressures to pursue a course that has broad popular support, eschewing pragmatic and long-term thinking. Therefore, the price we are likely to pay is a foreign policy excessively geared to short-term calculations in which domestic political considerations often outweigh sound strategic thinking.

To understand the importance of the mass media in the realm of foreign policy making, on the other hand, one need not to go beyond the classic literature on counter-insurgency; that is, the perception of reality is as important as the reality on the ground.

Mass media are the deliverers of a message through which audiences comprehend and indeed form opinions on events; a process known as agenda-setting. In this way, it is no exaggeration to claim that the media have inevitably become an instrument of war. Winning modern wars is as much dependent on carrying domestic and international public opinion as it is on defeating the enemy on the battlefield. This is such a given that success in the information age is defined in political rather than military terms.

Prominent among the consequences of agenda-setting effects is the priming of perspectives that subsequently guide public opinion on public figures. By calling attention to some matters while ignoring others, television news as well as other news media influences the standards by which governments, presidents, policies, and candidates for public offices are judged.

Given the role of the media in agenda-setting and shaping public opinion, it is thus an absolute necessity for media coverage of terrorism as well as the war in Afghanistan to start focusing on the role of economic development and the need for long-term planning as the best way toward de-radicalisation. In this way, politicians will find it easier to commit to long-term planning. After all, there should be no illusion about the fact that the media prepares the public mind.