Dehemlocking the Deal

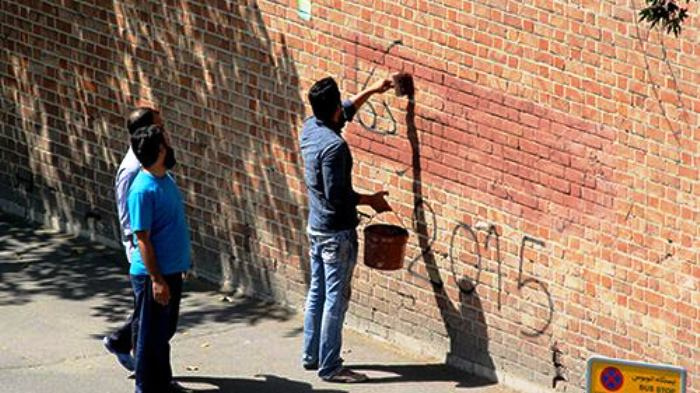

(Photo: man removing a slogan reading "Death to America 2015" from the walls of the former US Embassy in Tehran/ Farda News)

By: Ali Attaran

On July 18, 1988, roughly one day after the issuance of UNSCR 598, Ayatollah Khomeini decided to endorse the resolution and put an end to military confrontation with Iraq. Eight years of attritive war had taken their toll on the country. To make the situation more complicated, Washington had also decided to assume a more active role in aiding Iraq.

Ayatollah Khomeini’s decision came as a shock to revolutionary forces, who for years had voluntarily fought against Saddam Hussein’s brutal army. (“I ran out of tears” recalls one war veteran.) With the increasing ideological polarization between the anti-Imperialist, pan-Islamic, revolutionary Iran and the secular, pan-Arab regime of Iraq, ending the “Sacred Defense” against Saddam Hussein’s army was a formidable decision that only Ayatollah Khomeini could undertake.

It was a painful decision for the ayatollah too. “I now consume the poisonous cup of Resolution”, he said in his letter of approval; yet he was prompt to assure his followers in the same letter that the larger battle was not over: “Today, the war between the Truth and the Vanity, poverty and wealth, the oppressed and the oppressors, and the bare-footed and the unsympathetic rich has [just] begun.”

Drawing parallels between the nuclear saga and the eight-year war has always tempted Iran observers and analysts. The comparison has particularly been a favorite rhetorical instrument for two ends of the extreme, i.e. the pro-regime hardliners and counterrevolutionary critics.

Hardliners regard the endorsement of Resolution 598 a mistake, or in revisionist interpretations of the recent years, a likely machination led by Hashemi Rafsanjani and his accomplices to misinform Ayatollah Khomeini and convince him to approve the resolution. For counterrevolutionary forces, only two scenarios exist: either Iran withstands pressure from world powers, which means it does not understand how international relations work, or it opts for reconciliation, which means it has finally ‘surrendered’, as it did after eight years of war with Iraq.

One has to go to great lengths to compare the Vienna Deal with Resolution 598. Compared with the 1980s, Iran is now more realistic and knows the ropes, by and large. Although ‘saazesh’, reconciliation, still bears strong negative connotation in Iran’s political culture, negotiations are less strongly associated with weakness and surrender. Years of talks that culminated in the Vienna Deal were carried out under the close scrutiny of both the media and the public, hence little, if any, shock, and much more anticipation, for those who followed the trajectory.

Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, has handled the post-deal period in a fashion different from his predecessor, Ayatollah Khomeini: no expression of sorrow and no ‘cup of hemlock’. A realpolitiker, he has stressed that the nuclear deal, even if actualized, is what it ought to be, i.e. a ‘nuclear’ deal and not a step towards normalization of ties with the United States. He has frequently emphasized that Iran will not be morphed into a post-revolutionary state and will adhere to its regional policies, or in domestic terms, its support for the ‘resistance movements’ across the Middle East.

Hardliners, however, seem unrelieved. Alarmist by habit, they see the negotiated agreement as yet another hoax by Western countries to bring Iran into their orbit, strip it of its revolutionary capital of anti-Westernism and anti-Americanism and (taking a page from Huntington’s book?) put an end to the ‘civilizational battle’ between the Islamic Iran and the West.

In recent days, a ‘Burn the US Flag’ campaign has been launched, ‘Death to America 2015’ slogans have been painted on the walls of the former US embassy in Tehran, or in the most recent case, a marble monument has been set up in front of the US Embassy, listing one hundred negative epithets of the United States extracted from Ayatollah Khomeini’s speeches. Actual or purported, they appear traumatized by the end of an eleven-year diplomatic war, even if at least 65% of Iranians support the deal.