Why Is Bahrain’s Government Afraid of a Tweet?

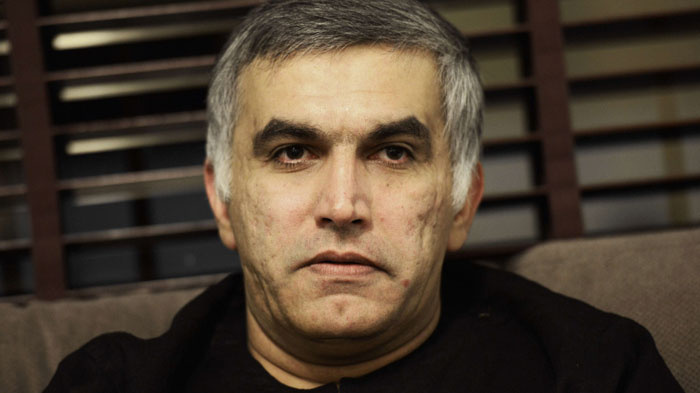

Editors’ note: Nabeel Rajab was arrested in October 2014 on charges relating to a series of tweets in which he accused Bahraini security forces of cooperating with the Islamic State. He was released on bail, but on April 2, 2015, was again arrested on new charges related to his comments on government treatment of prisoners. If the charges are upheld, he could be sentenced to up to 10 years in prison. He remains in detention; this article was written for Foreign Policy before his April 2 arrest.

Imagine, for just a moment, if a U.S. soldier left his post to travel to Iraq and join the Islamic State. Imagine that he filmed himself in Iraq as proof of his defection. Imagine if it then emerged that the Department of Defense was distributing books and materials, which spread hateful ideologies that encouraged the soldier’s defection.

What would happen?

American society would immediately self-reflect: What led our serviceman to join the jihadi group? Where did the United States go so wrong, to produce terrorists out of soldiers? The press would demand answers from the government. The secretary of defense would be compelled to make a statement; maybe the president would, too. They might argue that the evidence is refutable, but their political opponents and the public would demand an adequate explanation. An inquiry might be launched. Due process would be followed.

Eventually, a respected conclusion would emerge. It might find that the government was responsible, or partially responsible, for the spread of hatred and inculcation of terrorist ideologies and tighten regulations. Someone might lose his or her job, or even be brought to criminal prosecution. Or the inquiry might exonerate the government and Americans could rest on the knowledge that, against severe public scrutiny, the United States successfully demonstrated the integrity of its armed forces.

If that scenario seems unrealistic, then know that something very similar to what I described has happened in my home country — Bahrain. Except there, the government engaged in no such self-reflection.

Last year, four Bahrainis traveled to Iraq where they joined the Islamic State. In a video filmed and uploaded on YouTube, they call on their fellow Bahrainis to join the terrorist organization. One of them, Mohammad Isa Albinali, formerly a lieutenant in the Ministry of Interior and going by the name Abu Isa Al Salmi, looks straight into the camera and declares King Hamad of Bahrain, the prime minister, the crown prince, and the government of Bahrain infidels for their alliance with the United States and for leaving in peace “Rejectionist” Shiites in their husseiniyas, where they “insult” Islam and Islamic figures.

Around the same time, two books published by the Ministry of Defense were leaked to the press and to my organization, the Bahrain Center for Human Rights. One was titled The Light of the Sunni Faith and the Darkness of Heresy, another The Light of Unity and the Darkness of Paganism. Later, I acquired a Saudi Arabia-published book at the Bahrain Defense Forces library titled From the Doctrine of the Shiites.

These books describe Shiite Muslims as “Rejectionists,” a favored term among hard-line Sunnis, and present our ideology in a twisted fashion, to appear as though we reject the fundamentals of Islam itself. A typical passage from From the Doctrine of the Shiites reads: “The Rejectionists, who in our era are called Shiites, say that the Quran we have is not the one which was received by the Prophet Muhammad, but has been changed, added to, and had parts removed from it.” This is inflammatory for all Muslims, who believe the Quran to be the unchanged word of God.

The majority of Bahrain’s citizens are Shiites, estimated at up to 60 percent (exact figures do not exist). But the overwhelming majority of the security forces are Sunni, many of them recently naturalized Pakistanis, Yemenis, Syrians, and Iraqis. These men are imported to Bahrain for the express purpose of filling the rank and file of the Bahrain Defense Force and the police. They are regularly deployed to break up protests in the streets of Bahrain. The majority of protesters are Shiites.

The math is simple: The police and army are almost all Sunni, predominantly clashing with Shiite protesters.

Government ministries distribute texts vilifying Shiites to the police and army. An estimate of 100 Bahrainis have gone to join the Islamic State, at least one of whom, but possibly more, have come from the security institutions. Bahrain’s security forces demolished dozens of Shiite places of worship in 2011. The Islamic State, for its part, is hateful of all Islamic sects and thoughts which do not align with their own and have demolished Shiite mosques and national heritage sites alike. How the terrorist Mohammad Isa Albinali considers the Bahraini government to be protectors of the Shiite is beyond comprehension, considering the evidence. But then, it seems that nothing short of genocide is enough for Islamic State.

On Sept. 28, 2014, I tweeted the evident conclusion: “many #Bahrain men who joined #terrorism & #ISIS came from security institutions and those institutions were the first ideological incubator.”

On Oct. 1, 2014, police arrested me and charged me with insulting the Ministries of Interior and Defense. In January, the criminal court sentenced me to six months imprisonment for my tweet, a sentence which the appeal court will decide whether to uphold or acquit me of on Tuesday, May 5.

Meanwhile, Bahrain’s government has made no move to stem the tide of homegrown terrorism. Not only does the government continue to distribute hateful books, but Islamic State sympathizers are allowed to freely advocate on the terrorist group’s behalf without suffering any government response. If you are a supporter of the Islamic State, you can find forums and write your thoughts about the terrorist group’s latest battlefield victories and defeats. Meanwhile, the Bahrain Center for Human Rights’ website has been blocked by Bahraini Internet service providers since 2006.

Bahrain has extremely tough anti-terrorism laws. Suspects can be detained up to six months before they see a judge, and over 70 people have been sentenced to life for terrorism — in most if not all cases, the defendants were tortured and coerced to confess. But the government has not targeted Islamic State sympathizers or financiers with these laws. Instead, the focus has been on local street protesters. The law also allows the state to revoke the citizenship of terrorists, and in January the state stripped 72 people of their citizenship, around 50 of whom were human rights activists, journalists, bloggers, religious clerics, and opposition activists. The rest were actually terrorists who had joined the Islamic State or al Qaeda affiliates in Syria, but their inclusion with peaceful rights activist says more about how Bahrain considers the civil rights movement and political opposition than it does their commitment to fighting terrorism.

This presents an unresolved dilemma. Bahrain, like Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates, is a member of the U.S.-led coalition against the Islamic State, but the government in Manama turns a blind eye to supporters of jihadi groups. In February, Bahrain sent fighter jets to Jordan to help bomb Islamic State-held territories in Syria in response to the barbaric immolation of Jordanian pilot Moaz al-Kasasbeh. Yet it is doing nothing to stop indoctrination at home. Saudi Arabia was perhaps the first country to see the tragic consequences of this contradiction, when in November Saudi Arabian al Qaeda fighters returned home from Syria and opened fire on a Shiite mosque in the Eastern Province, killing seven.

The United States, Britain, France, and other major parties in the war against the Islamic State also face a dilemma. They are working with Bahrain and other Gulf countries to bring security and stability in the region, yet they have been ineffectual in stopping the flow of men and cash from these countries to Iraq and Syria. Qatar and Saudi Arabia have been the most heavily criticized for their contradictory role in the operations, but Bahrain deserves to be in the spotlight, too. Not just because it is allowing terrorists and their supporters freedom, but because it is using most of its antiterrorism capacity against mostly peaceful activists.

When Bahrain would rather imprison me for calling out their idiosyncratic security policies rather than address those policies, how can the United States work with them to eradicate the Islamic State? Ultimately, the United States, Britain, European countries, and other powers need to put further pressure for their Gulf allies to challenge terrorism at home. Or else, the cycle of violence will only perpetuate and spread.

Source: Foreign Policy