Muslim “Rage” and the US Presidential Election

It should be an article of faith that US presidential elections are only nominally affected by foreign policy or by events that occur outside the US, excepting of course, American involvement in wars, believable threats to the security of Americans on the home front, and terrorism that affects US citizens. But on the anniversary of 9/11, events in the Middle East had the potential to turn foreign policy into more of a key issue in the presidential race, with protests over a supposed film (which, except for its trailer, has so far been unseen by anyone) on the life of the prophet Mohammad turning violent with attacks on US embassies in the Muslim world and resulting in the deaths of four Americans in Libya, including the US ambassador to Tripoli.

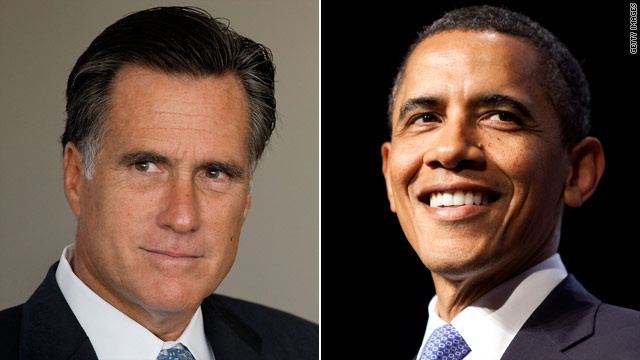

Republican Mitt Romney, in another one of his foreign affairs gaffes, immediately responded to the attacks on the US Embassy in Cairo by accusing President Obama of siding with the protestors outside the gates, because of a tweet staffers sent out before protestors attacked the embassy (which, unlike at the consulate in Benghazi resulted in no injuries or deaths to Americans) which disavowed US government complicity in the making of the film or its trailer, and condemned it for its intolerance. Romney’s foreign policy theme of “never apologizing for America” was central to his argument, which fell flat with the US media, with pundits, and probably with most Americans, mainly because nothing in the US embassy tweet could be construed as an apology, because of the well-established fact that the tweet was sent out before any attacks on US property or personnel, and because of the insensitivity of commenting at a time when Americans, who helped bring about the freedom to protest in Libya, were dying. Nonetheless, Romney, who is aware that most Americans don’t pay much attention to international news and rarely consider foreign policy as a bellwether issue in choosing a president, is also aware that Islamophobia is rampant in America, and that his portraying an administration as indifferent to the threat of radical Islam might resonate with a segment of society. In the 24 hour American news cycle, however, it is unlikely that this one gaffe, whether perceived as one by his supporters or not, will have a lasting effect on the presidential race.

The week after the deaths of US diplomats in Benghazi, though, Newsweek magazine splashed a headline on its cover that could reignite the debate over whether American policy in the Middle East is on the right track, or not, as Romney maintains. The headline, “Muslim Rage”, and the cover story written by the famously Islamophobic Ayaan Hirsi Ali, immediately became the target of liberals and mainstream American Muslims (who expressed their dark humor on Twitter feeds), but it also fed the mainstream public’s fear of radical Islam, if not of Islam itself or of Muslims in general, and of how political Islam might affect Americans. Viewing Muslims as “the other”, as being opposed to American values such as free speech, as generally undemocratic and as being prone to violent rage is not new in American discourse, but renewed attention to the issue at a time when most Americans are either undecided on whether the Arab Spring is good for the US, if they care at all, or are questioning what future US policy toward the Muslim world should be, especially if one throws in the Iranian nuclear issue, could have some effect on the election, and will certainly figure in the one presidential debate that is scheduled to focus on foreign policy.

With the UN General Assembly in session, and with heads of state, including President Ahmadinejad and Prime Minister Netanyahu, descending on New York next week, foreign affairs and particularly as they relate to the Iranian nuclear issue and the so-called “Muslim Rage”, will undoubtedly continue to hold the interest of the US media and the presidential candidates for the rest of the month. President Obama’s speech will be scrutinized by the media, and by the Romney campaign for any openings to attack the administration; Netanyahu, who has already equated the attacks on US embassies with Iranian irrationality in its behavior, will be largely focused on the Iranian nuclear issue, and President Ahmadinejad will have an opportunity to either alleviate some of the concerns of the West, or once again inflame emotions with his speech. It will probably be the most important speech of his career, and not because it will be his last one in New York. What Mr. Ahmadinejad decides to say; about the Muslim reaction to the anti-Muslim film, about Israeli threats to attack Iran’s nuclear sites, about the red lines that Netanyahu has described, and about Iran’s intentions—with regards its nuclear program, Syria, and overall Middle East issues— will have an impact on the US presidential race and provide talking points for both candidates in their public statements and in their debates, as well as an impact on the Western approach to relations with Iran, no matter who wins the US presidential election.