The Iranian Revolution Was Primarily a Non-violent Movement

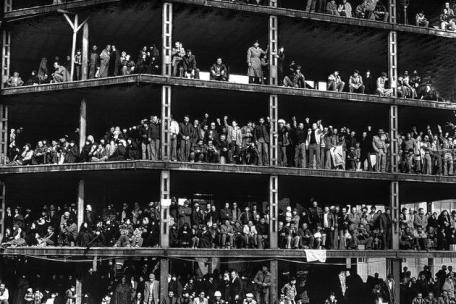

( Photo: protesters gather inside a half-constructed building located in the Eisenhower Street -later Freedom Street, chanting, as their fellow demonstrators trod the path towards the Shahyad Square -later Freedom Square. The building gained an iconic status after the Islamic Revolution.)

John Foran is professor of sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. His current areas of interest include the comparative study of 20th-century revolutions and 21st-century radical social change, development, climate, and globalization, and the global justice and climate justice movements. His books include Fragile Resistance: Social Transformation in Iran from 1500 to the Revolution (Westview, 1993; available for free on the departmental website), A Century of Revolution: Social Movements in Iran (editor, Minnesota, 1994), Theorizing Revolutions (editor, Routledge, 1997), The Future of Revolutions: Re-thinking Radical Change in an Age of Globalization (editor, Zed, 2003), Feminist Futures: Re-imagining Women, Culture and Development (co-editor, Zed, 2003), Revolution in the Making of the Modern World: Social Identities, Globalization, and Modernity (co-editor, Routledge, 2008), and On the Edges of Development: Cultural Interventions (co-editor, Routledge, 2009).

In his most recent book, Taking Power: On the Origins of Revolutions in the Third World (Cambridge, 2005), he presents a new theory of the causes of revolutions across three dozen cases from Latin America, to Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, and spanning the period from 1910 to the present. The book has won distinguished scholarship awards from the Pacific Sociological Association, and the Marxist and Political Economy of the World System sections of the American Sociological Association.

He is currently working on his next book, Taking Power or (Re)Making Power: Movements for Radical Social Change and Global Justice.

The edited transcription of this interview is a courtesy of Tarikh-e Irani (Iranian History).

IRD: Most political or social analyses of the Iranian revolution find the roots of revolt in economic issues or the desire of society for Islamic values -- that the revolution happened only because Iranians were angry about anti-Islamic aspects of the Shah’s administration. We see fewer analyses which refer to the desire for democracy, for having representation in parliament or democratic justice -- values that Iranians have shown they are interested in since the Constitutional Revolution in 1906 or in voting for Mohammad Mossadegh in the 1950s. Why do so many studies of the 1979 revolution point to economic, religious or anti-colonial factors?

JF: In part, the answer is that the revolution in fact did heavily involve “economic, religious or anti-colonial factors.” From an intellectual point of view, studies of revolution in general have typically underplayed the role of human agency, and of what I call “political cultures of opposition and resistance” in particular. In Fragile Resistance, I argued that there were at least five competing political cultures of resistance, three Islamic, and two secular: 1) [Ayatollah] Khomeini’s “militant Islam,” 2) Shariati’s “radical Islam,” 3) Bazargan and his movement’s “liberal Islam”, 4) the Marxist opposition of the Farda’s and Tudeh organizations, and 5) the democratic/liberal nationalism of Mossadeq.

Of course, there are also political and ideological reasons for the situation as well: Marxists will emphasize anti-imperialism and economics, Islamic activists will see mainly the role of [Ayatollah] Khomeini and the militant ulama [religious scholars], etc.

IH: How non-violent was the revolutionary movement? Could we consider it a peaceful movement?

JF: This is a good question, and my answer is that yes, the Iranian Revolution of 1978-79 was primarily a non-violent movement of unarmed demonstrators in the streets of Tehran and other cities facing the Shah’s army, combined with the non-violent strikes of the oil workers. The violence came from the side of the state, not the opposition. A small current of armed guerrillas – Islamic and Marxist – had played important roles in the 1970s, and a small role in the final overthrow of the shah on February 9-11, 1979.

IH: One of the criticism on your ideas about the Iranian revolution has to do with the concept of the “world opening,” and its implication that if the world powers had stood against the wave of Iranian revolt, the revolution would not have won. On the other hand, some researchers say that although the Carter administration pushed the Shah to change his policies against human rights, until the last months of the revolution the US supported Shah’s regime. Nevertheless the revolution was able to overthrow the regime. How would you explain this paradox?

JF: I don’t think that the revolution would have failed if the United States had supported the Shah more aggressively during the last eight months up to February 1979. I do think that the outcome would have been affected by unwavering support from the United States – more violence from the Shah’s army, perhaps a military coup against the Shah, etc. – and this would have affected the timing, and possibly the nature of the revolution in ways that are difficult to know. The movement did, in fact, gain strength precisely at the time that the US stepped back from the Shah in the fall of 1978. I believe that this world-systemic opening, this let-up of the support for the regime by a major world power, was one among several factors that weakened the regime and strengthened the revolutionary opposition.

IH: In the coalition of social classes against Shah, which classes were involved in 1978 revolutionary movements and how important were each of these classes in the overthrow of shah? Which classes or social groups got the upper hand in the revolutionary movement?

JF: I argue that the revolution was made by a broad, multi-class revolution, consisting of urban workers (the oil strikers), the secular and religious professional class of teachers, artists, writers, and ulama, the urban middle classes who were hurt by inflation and wanted a more democratic Iran, and the urban poor to some degree, without whom the demonstrations would not have been as large. All were important in overthrowing the Shah, and their coming together in opposition was the key to the revolution’s success. Afterwards, the ulama and a section of the Iranian urban and rural elite ended up with power, and the workers, urban and rural poor, and middle classes benefited only to a limited degree. Iran remained part of the capitalist world economy after the revolution, and it is not surprising therefore that the above-mentioned classes gained the most. This is not to say that many Iranians didn’t get some benefits from the revolution, but much of what could have been achieved was lost when the war with Iraq consolidated the power of the ulama and other elites around [Ayatollah] Khomeini and at the same time undermined the potential for economic growth and redistribution.

IH: The revolutionary movement benefited from a charismatic leader who was supported by most of social and political opposition forces. Was the movement which rose and spread in 1978 able to overthrow the Shah without that kind of leadership, as happened last year in Tunisia and Egypt?

JF: It’s impossible to know if the movement would have succeeded without [Ayatollah] Khomeini’s symbolic and political leadership, and that of the organization of ulama that represented him in Iran. What we can say is that without [Ayatollah] Khomeini’s opposition, or if Shariati had lived, things would have been different, yes, definitely. The role played by [Ayatollah] Khomeini, and his unifying demands that both the Shah and US influence must go, were essential for the revolution to succeed.

IH: In the 1980s one of the disputed issues between you and other sociologists such Theda Skocpol about revolutionary movements was about Skocpol’s claim that “Revolutions are not made, they come.” I think at least in the case of the Iranian revolution you wouldn’t agree with Professor Skocpol. What is your position?

JF: Skocpol herself acknowledged that the Iranian revolution was, in part, “made” when she analyzed it as early as 1980. My difference with her is not so much about Iran, but that I feel that all revolutions in human history have been “made” by the actions of people as well as the large, impersonal structural factors that she has emphasized in her theory of revolution. In other words, she saw the case of Iran as an anomaly, and I made what I had learned about the causes of the Iranian revolution the center-piece of my approach to all Third World revolutions.

IH: Another disputed issue is about the role of the working class of Iran in the revolutionary movement. Despite the belief of many that the revolutionary movement would not have been able to overthrow the regime without involving the working class, some Iranian sociologists such Dr. Ahmad Ashraf says this class entered the protests only after the massacre of Jaleh Square in September -- the third stage of the revolution – and from that point to February 1979 many workers were still indifferent about the revolutionary campaign. What is your view about the role of the working class in the Iranian revolutionary movement?

JF: It would be foolish to deny that the general strike in the oil sector was necessary to bring down the Shah. What’s true is that the oil industry only accounted for a small percentage of all Iranian workers. On the other hand, workers in other sectors played a role in strikes, and the crowds in the biggest demonstrations contained many thousands of workers.

IH: It seems that in the years leading up to 1978, no expert, university professor, official or Western diplomat predicted the collapse of the Shah. Why was the rise of Iranian revolution movement so unpredictable in Western countries? What happened in Iranian society which suddenly found out it could no longer tolerate the Shah's regime?

JF: Very few revolutions in world history have been predicted by scholars or foreseen by others. Iran is no exception in that regard. What scholars only explain why revolutions have happened after they have succeeded. There is nothing surprising about this to me because revolutions require the coming together of a number of factors that rarely come together in the same society at the same time. In an article in Third World Quarterly in 1997 I made some “guesses” about the possible futures of revolutions in the new century, and I did successfully identify the overthrow of the Mexican government through elections and the fall of the Mobutu dictatorship in Zaire. I also argued that both Cuba and Iran would be stable, which they have been. But I don’t believe that we can, in fact, predict social movements or any phenomena that require the action of people – such phenomena do not follow law-like rules, or at least, people have the capacity for a much broader range of outcomes than our theories predict.

IH: To Gorbachev's Prime Minister Nikolai Ryzhkov, the “moral [nravstennoe] state of the society” in 1985 was its “most terrifying” feature: “[We] stole from ourselves, took and gave bribes, lied in the reports, in newspapers, from high podiums, wallowed in our lies, hung medals on one another. And all of this -- from top to bottom and from bottom to top.”

Was there the same condition also in Iran 1978? Did Iranians feel that the government ruled in a way that would lead to its moral downfall and did this belief contribute to a revolutionary irritation and anger?

JF: It is pretty clear that there was significant corruption at all levels of the government and the economy, as is the case in all dictatorships. The moral anger of the broad coalition that made the revolution derived in large measure, I think, from an effect of this corruption, which was the glaring inequality that grew up in Iran in the quarter century of the Shah’s reign: people could see the minority of the well-to-do improving their life chances and circumstances, while the vast majority’s lives got measurably worse, in terms of housing, nutrition, health care, education, and most measures of social and human quality of life and well being.

IH: How effective were liberal democratic institutions in the revolutionary movement in Iran? How hopeful were Western sociologists that this movement eventually would create some kind of reliable democracy?

JF: I can’t speak for others, but my view of the long run of Iranian history is that there have historically, since at least the Tobacco Revolt of the 1890s, been strong social movements for greater political participation and economic equality, including the Constitutional Revolution of 1905-1911, the Kurdish and Azarbaijani movements of 1945-46, the oil nationalization period under Mossadeq, the Iranian revolution of 1978-79, and the movements of students, middle and working classes for the same goals since 1979, including the Green Revolution of 2009.