Open-Ended Elections and Musavi’s Future

Musavi stood against obstacles as he had promised. But his future after this open-ended election depends on power equations inside the establishment.

Calling it an ’open-ended’ is not devoid of meaning. The tenth presidential election is not over even after the final approval by Council of Guardians. The discontent nominees have not retracted even one step in their recent statements, rather turned more radical. They showed they will not step back from their objection and consider the status quo unjust.

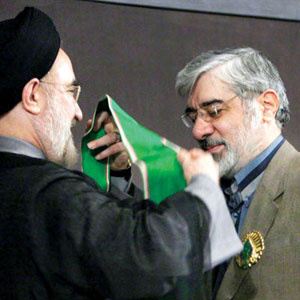

The eyes are mainly on Mir Hosein Musavi. After 20 years of living in the margin of Iranian politics, he welcomed the request of political groups and figures and came on the stage with a dual face: reformist and principlist. The course of events developed in a way that brought Musavi a status beyond a presidential nominee. He found a new level of prestige, and as he said in his 9th statement after the elections, turned into the voice of new social demands. Undoubtedly, neither Musavi nor his supporters could imagine that his name would be shouted in nightly allahu akbar’s on rooftops and turn into a symbol of protest.

While Musavi’s insistence on election fraud led to street riots and urban clash among his supporters and security forces, a new project was set up against him; one that his foes thought of as his inescapable fate. The poignant events after the elections paved the way for diminishing Musavi. Media run by either the state or his opponents tried to provide the circumstances for Musavi’s detention, house arrest or isolation.

Even now this may be Musavi’s inevitable destiny. Those who belong to the revolution first generation and remember the early struggles after the 1979 uprising can better appreciate the analogy between Musavi and Abol-Hassan Bani Sadr [the first Iranian president] which counter-reformists apparently savor these days, disregardful of Musavi’s revolutionary record and his intellectual origins.

The more moderate believe that a future similar to Ayatollah Hosein Ali Montazeri awaits Mir Hosein Musavi after the turmoil settles down. With the efforts to extract confession from reformists, it would be no surprise if Musavi were introduced as the culprit of recent events, forced to isolation and called naïve, like Montazeri, so as not to offend his supporters.

If one bothered to read some [counter-reformist] newspapers these days, they could easily predict the upshot of political developments, especially protests and unrests, and how they will be ’solved’.

A view at the course of events in the tenth presidential elections would evince that objecting candidates, particularly Mir Hosein Musavi, should not have hoped for any annulment or change in the result of elections. Definitely Mir Hosein Musavi had found out what was going on since the night before the elections so even in days when he persistently called for dissolution of elections and released his statements, he knew well that nothing would change but implications of his insistence would be important.

However, 20 days after the protests, the time has come for Musavi to pay the price. State-run TV and newspapers are successively publishing reports in which people, officials and analysts accuse Musavi of fomenting disorder and claiming that while his election slogan was abidance by the law, he is the biggest law-violator.

If we admit that the protests will be open-ended, and we admit that neither Musavi and Karrubi nor their supporters have accepted the election results, and regard it as a forced result, we must also admit that the only way to extinguish the reform movement is blaming all the problems on Musavi and Karrubi, and homebounding them, which equals their political death.

The other side of the coin arouses interest notwithstanding. Musavi’s last statement has convinced some analysts that he wishes to continue his political career and set up a political party. Clearly Musavi has a considerable potential –even more than Mahdi Karrubi- to run a party. While having the support of revolutionary and principlist figures, who mainly come from the first generation of revolution and have been the disciples of Ayatollah Khomeini and Ayatollah Beheshti, as a modern thinker Musavi is a popular figure among reformists, consequently among the urban middle class and cultural elite.

Musavi possesses the basic requirements for establishing an Iranian party, i.e. supporters in power loci, university and cultural elite, social base among the young and middle-aged, supporters with international prestige and parts of the society. In fact, it was the tenth presidential election that gave Musavi the opportunity to found a party and sustain a political and social movement. What he gained from this election can cover up what he lost to some extent.

Meanwhile, Musavi should not confuse his personal charisma with his social and political capital, and try not to rely on it. Now he should seek ways to stay in Iranian politics. Power circles which fear the potential of Musavi and his supporters will not allow him to follow an effective political career, since in that case they should anticipate any sort of change in future, and if another turning point, like Khatami’s election in 1997 or the uprising after June 12th election, happens again they will not forgive themselves.

Musavi’s step into party politics means that there is no end to post-election protests. If the bargain made by his supporters in power loci –Rafsanjani, Nategh Nuri, and to some extent Larijani- proves efficient, Musavi can be hopeful to remain on the political stage. But nobody hears the voice of Musavi’s insider supporters these days. The silence and caution of these figures means that they prefer to maintain their position inside the system, implying that Musavi will be ousted from politics. So far no sign of Musavi’s political survival is visible and evidence suggests that his political death is near.