How Tehran is ramping up a trade offensive

By: Majid Rafizadeh

Since 1979, Iran has positioned itself in strategic competition with its neighbours, primarily Saudi Arabia. One of Iran’s major tactics has been to seek to gain popularity and exert influence through soft power.

Before the Syrian uprising, Iranian leaders, in contrast to the American political establishment, implemented strategies to expand their influence in the Middle East and establish relationships through soft power.

Culturally, Iran enjoys shared societal norms and national festivals with some of the population in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Turkey, Lebanon, Yemen and Syria. Religiously, the Shiite communities across the region have affinities with Iran.

When it comes to policy, particularly foreign policy, in order to shape public opinion and create alliances, Iranian leaders have adjusted their focus to place an emphasis on independence, self-determination and resistance.

The leadership in Tehran has projected Iran as the only country in the region that has been free from the chains of American and western policies.

Finally, the Islamic republic continues to invest in shaping public opinion via education (bringing many foreign students to study in Iran).

Nevertheless, things have changed in the past few years, since the Syrian uprising.

Recently, Iran found itself obliged to use hard power, by deploying the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and its military branches more forcefully across the region, specifically in Syria, Iraq and Yemen.

Iran’s foreign policy and rhetoric have raised concerns about Iran’s ambitions. Its meddling in the internal affairs of countries has became more public, resulting in heightened tensions.

Iran’s foreign policy and deployment of hard power significantly neutralised its soft power success story. For instance, most recent polls highlight how people across the region view Iran as a threat, rather than a role model.

Iranian leaders, aware of shifting perceptions, began to search for other approaches to expand their influence.

Global legitimacy became the tool. Iran enjoys Russian and Chinese support, but it needed the West since global legitimacy is usually tilted towards acceptance of western powers towards that particular state.

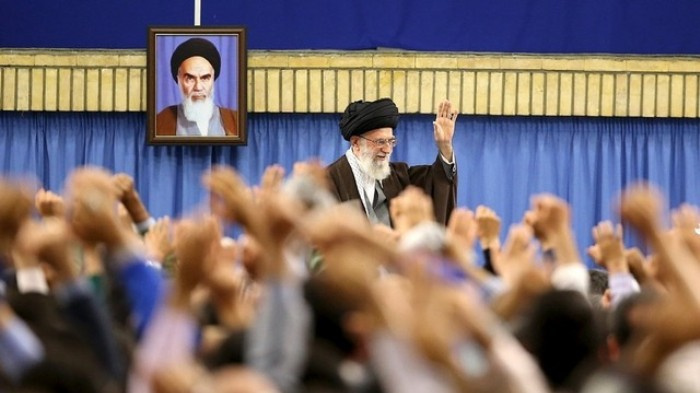

Since Iran’s supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, and the senior cadre of IRGC are not going to fundamentally change their foreign policy and ideological objectives to appease the West, they skilfully shifted their focus to trade.

Trade and business with the West can be a powerful tool to raise a particular state’s legitimacy without having to push the politicians of that country to liberalise or change their politics.

Through its foreign ministry and major stockholders, Tehran is ramping up trade with European countries.

The EU strongly welcomed this new trend and even agreed to respect Iran’s Islamic rules when Iranian politicians would visit their countries. This economic and political trend is going to increase.

Trade with Europe grants Iran some of the legitimacy it desires. This also allows Iran to avoid being criticised by the West for its regional foreign policy.

From the Iranian leadership’s perspective, greater global legitimacy would, it believes, force the region to view Iran as an independent powerful model. Through this acquired legitimacy, Iran would attempt to exert its influence over its neighbours.

As Iran’s global legitimacy increases through trade with the West, Tehran believes the people in the region will begin respecting Iran more, which will, in turn, improve Iran’s influence and expansionist goals in the region.

This is a powerful tactical shift in Iran’s policy to compensate for their negative role in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen.

Dr Majid Rafizadeh is an Iranian-American Havard scholar and president of the International American Council on the Middle East.

Source: The National